Productivity

A System for Writing: How an Unconventional Approach to Note-Making Can Help You Capture Ideas, Think Wildly, and Write Constantly - A Zettelkasten Primer

Bibliography

- Author: Bob Doto

- Full_Title: A System for Writing: How an Unconventional Approach to Note-Making Can Help You Capture Ideas, Think Wildly, and Write Constantly - A Zettelkasten Primer

- Category: books

- Document Tags: [ productivity, ]

- Last Highlighted Date: 2024-10-05 01:27:07.221878+00:00

Highlights

- Fleeting notes form the basis for much of what you’ll create inside your zettelkasten, though they themselves will not make it past the velvet rope. Fleeting notes live in a state of potential, waiting to be transformed into more useful “main notes,” the notes that will make up the bulk of your zettelkasten.

- Any notes that seem hard to process, but are still relevant to your thinking, should be moved to a “Sleeping” folder.

- depending on how feverishly you capture thoughts, it’s possible the majority of your fleeting notes will end up either in the waste bin or ignored.

- Note-taking is writing, and writing is a path toward knowing. Taking fleeting notes is the first step in knowing what you think and believe.

- A reference note is a single long-note containing brief citations or “references” to what caught your attention while reading a book, listening to a podcast, watching a video, or having a conversation.

- As you spend time working with your zettelkasten, you’ll begin gravitating toward ideas and passages in your reading that speak directly to others already stored in your slip box.

- Read with a question or problem in mind.

- Capture ideas you disagree with.

- Capture what you think about what the author thinks.

- Reader-response theory posits that no one person, not even the author, has a monopoly on the meaning of a text. Rather, meaning is created through the act of reading.

- Capture someone else’s interpretation.

- Don’t forget fiction.

- Go wild with your captures.

- The most important thing about any form of reference note-making is to, at some point, return to the note. It’s the “going back” that makes all the difference, understanding that your initial scribble isn’t the end of the capture. It’s the beginning. A reference note is to be used as a reference. Its contents to be transformed into main notes.

- Like fleeting notes, not everything you capture in a reference note need be transformed into a main note.

- If you tend to read digital books, you can still do the steps above, but also have the option of using one of the many “read later” apps to store your highlights and notes. If you use this approach, I recommend bringing these captures into a separate reference note file, as notes stored in read later apps can quickly pile up and become unpleasant to work through.

- In its most basic form, a main note should have at least two components:

• a single idea, and

• a link to another idea stored in your zettelkasten

- Other elements that can be included in your main notes are:

• a title

• a quote or reference to where the idea comes from

• a record pointing to where and how the idea has been used in your writing

• a unique ID

- A main note works best when the thought contained inside has been pared down to its essentials. Having a single idea to contend with means you won’t be sifting through counterarguments and varying points of view. Instead, you’ll be dealing with a single unit of information that freely associates with others (4.5)

- Links are used to establish relationships between ideas. By connecting thoughts, we give ourselves options, turning isolated, single-idea notes into long-form trains of thought.

- A title acts as a condensed thesis summing up the content of the idea stored in the note.32 It should be a declarative statement rather than a descriptor.33 “Not all apples are edible” is a better title than “Apples and edibility.”

- Whenever you have an idea that’s built off of, or speaks directly to what someone else has said, bring the quoted passage into your main note.

- The more connections you make, and the more writing you create from these connections, the more important it’ll be to track how and where an idea has been used in your writing.

- alphanumeric IDs, sometimes called folgezettel,36 give notes a permanent identity that can be referenced regardless of any changes made to the note’s content.

- Processing Your Inbox and “Sleeping” Folder

- If the idea is one you aren’t ready to examine, send it down to your “Sleeping” folder

- Creating Main Notes from Fleeting Notes

Retype or copy/paste the idea into a new file, rewriting it if necessary, using complete sentences that capture the crux of the thought you’re trying to convey. Consider if/how this idea relates to another already stored in your zettelkasten. If the idea is unrelated to anything else, edit the idea so it’s readable, and import it without linking the idea to others. If the idea relates to another already networked in your slip box, either rewrite it to speak directly to the other idea, or reference the previously captured idea and state why you’re making the connection.

- Creating Main Notes from Captures in a Reference Note

The first thing to do when creating a main note from a reference note citation is to retype, copy/paste, or reference the quote you want to comment on in a new note.

- Creating Main Notes from Your Own Writing

While it may seem obvious that main notes will be created from passing thoughts and other people’s ideas, your own writing can also be used as a source for main notes. Blogs, articles, newsletters, tweets, emails, and comments on forums can all be parsed out and repurposed as main notes to be reused in other pieces of writing or thought work.

- If, when making a main note, a new idea comes to mind, take advantage of the opportunity to add it to your zettelkasten.

- It’s perfectly acceptable to incorporate questions into your zettelkasten, since these can serve as both placeholders for future answers and prompts for shorter writing pieces. But, questions left unanswered are a somewhat low-value form of content. After all, how will a question help you in your writing if you don’t know the answer? Where is the idea you want to get across? In order for questions to become useful, they need to be transformed into something usable.

One way to level-up a question is to embed it in a declaration. To do so, ask yourself why the question is important. What feelings does the question bring up? Is the question common?

- If you don’t know the answer, say what you know about the question.

- Whether you’re involved in a technical field, doing academic research, or just trying to keep track of what others have said about a topic, there are a variety of reasons why you may want (or need) to capture facts, definitions, and/or technical data in your zettelkasten. The trick is making this information usable and high-value.

- Restate facts in your own words.

- To enhance the value of captured facts, it’s best to rephrase them in your own words.

- Consider creating new notes so you can speak about the facts. By providing additional commentary, you can better integrate the information into your broader understanding of the topic, enhancing both your comprehension and your ability to write about the topic effectively

- Don’t be afraid to make it personal. You never know the value of a note until it relates to its familiars (3.7:2). The important thing is to bring the fact into contact with your own thinking.

- Regardless of the different kinds of information captured in a main note, creating these notes is generally achieved in one of two ways:

- Developing an idea “in light of” what’s already stored in your zettelkasten

- Developing an idea “in spite of” what’s already stored in your zettelkasten

- There’s always the possibility newly captured ideas will contradict or challenge others previously imported into your zettelkasten.

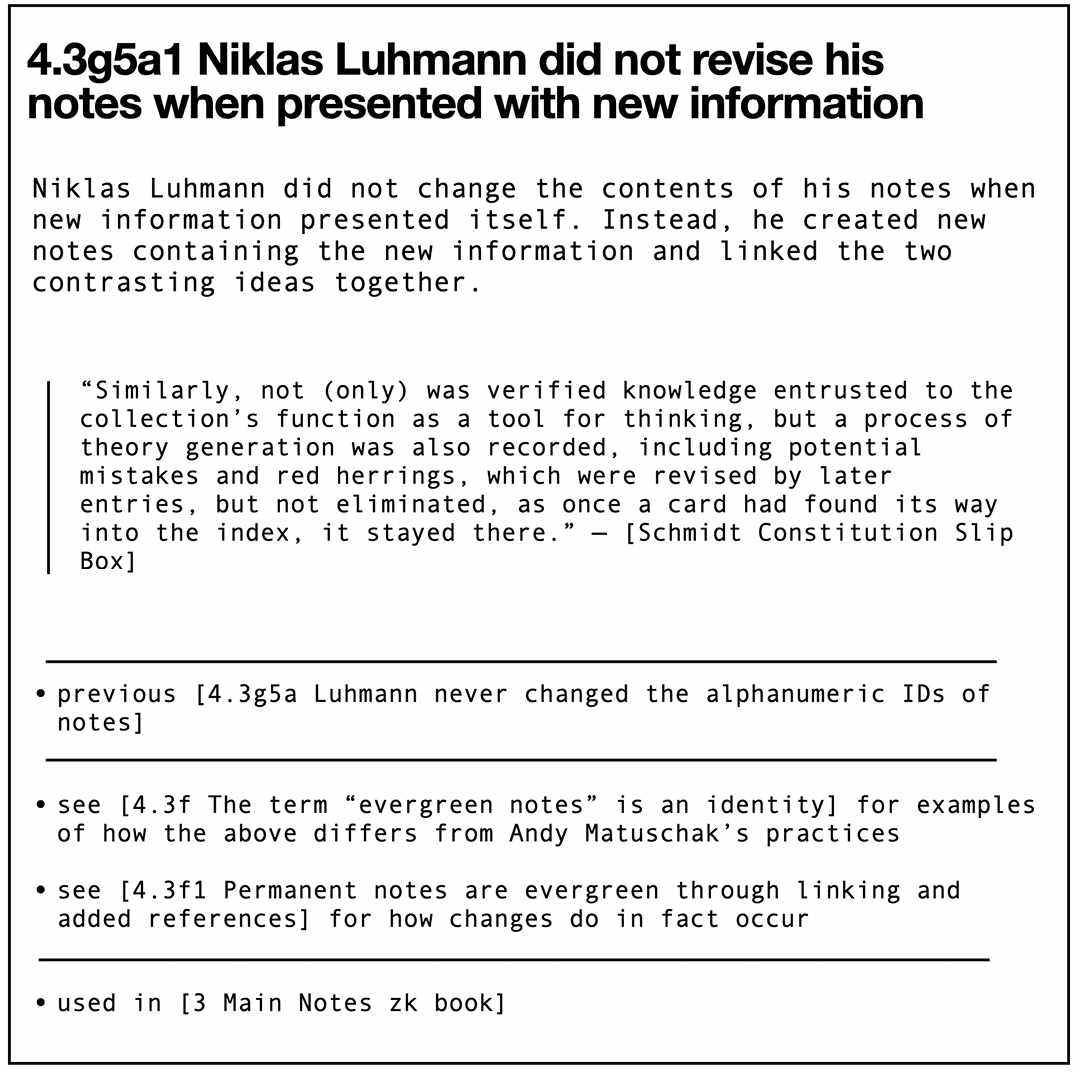

- Niklas Luhmann didn’t revise his notes when new information presented itself that contradicted previously captured thoughts.

- Instead, create a new note containing the counter argument, state why this new idea bests its predecessor, link the new note to the one it challenges, and import it into the zettelkasten.

- Must each main note be a perfect summation of your current thinking? The short answer? No.

- Relationships between ideas are what give them value.

- You don’t need to have it all figured out when creating main notes. Individual main notes don’t need to be perfect representations of your current thinking. They don’t need to contain the latest information, nor “all the links.”

- By interrogating ideas captured in main notes, new relevancies can be brought to light.

- At first, it may feel like the connections you’re making are strange, even forced. And, at times, they may be. But, as you add more notes, the ways in which ideas relate will become clearer.

- establishing relationships is the same: interrogate the content of your ideas. Read the subtext. Stretch their relevancy.

- What level of atomicity works best for you is personal. As a PKM comrade of mine has said, “make a note that contains the fewest number of pieces as necessary to be useful for its specified task.”

- Working with a Luhmann-style zettelkasten is, in part, a practice of decomposition, where a writer’s previously structured thoughts are disassembled, to be networked in the slip box, and reassembled later in new ways as a “mosaic of quotations.”53

- Sometimes one idea is really two.

- One rule of thumb is to keep an eye out for when “but” and “however” show up in your note-making. Whenever I write either of these two words while making a new note, I pause and ask myself, “Should what comes next be a new note?” The answer is (almost) always “Yes.”

- Embracing and leveraging the symbiotic relationships between connected ideas is the means by which we engage (and locate) our notes.

- Seeing folgezettel as a means to create hierarchy misinterprets what’s happening inside the zettelkasten. We aren’t connecting notes. We’re establishing relationships between ideas contained inside the notes.

- Folgezettel forces you to connect newly imported ideas.

- “Eufriction” is good friction.

Just as weight training, writing a book, and giving birth are considered forms of “eustress,”70 that is high-intensity activities that have beneficial results, so too is folgezettel a form of “eufriction,” a slowing down to better engage with the work in front of you.

- The main compartment of the zettelkasten is an anarchy of ideas: a personal knowledge base without hierarchy, without centers of power, without top-down structure.

- Luhmann believed non-hierarchical organization led to non-normative ideation. This, however, doesn’t mean Luhmann always engaged with the rhizome in its raw, anarchic state.

- Over time, recognizable areas of your zettelkasten will develop around particular themes and subjects. Hub notes help point toward the various places your thinking has gone, functioning as “access points,”78 or “highways between topics.”79

- Creating a hub note is relatively simple. First, choose a section of your zettelkasten where the theme has been taken into a variety of places via different trains of thought. Once you’ve decided on a section to work with, create a new note, and give it a name that identifies the topic you’ll be exploring. Next, identify which notes within the section initiate the various trains of thought.

- In contrast to hub notes, which contain lists of notes pointing toward trains of thought developing in your zettelkasten, structure notes are spaces where the contents of those trains of thought can be developed further. In order to see how your ideas relate semantically—how they might function as a coherent train of thought—they need to be exported to a place where you can unpack them. Structure notes are where this happens.

- Creating a structure note can be as simple as organizing a list of notes or ideas in a way that makes sense, added to over time, as new ideas come into the zettelkasten.

- This initial gathering of notes gives you something to work with. Once you’ve collected a few ideas, begin organizing them in a way that makes sense, giving context for the choices you make. Then, look through your zettelkasten for other ideas that speak to the developing theme of the structure note, once again giving context to the notes you’ve included. Fig. 44 shows what an evolved structure note can look like.

- Taking the time to organize and explain the relationships between the ideas you’ve collected will help you understand your own thinking on the topic, while at the same time leading to additional thoughts that can also be included in the structure note. You may also uncover areas of your thinking that lack substance or are missing completely.

- Hub notes and structure notes are, by design, relatively prescribed ways of engaging with the zettelkasten. Niklas Luhmann’s keyword index,87 on the other hand, functioned like an oracle.

Luhmann’s keyword index wasn’t exhaustive. At most, each listed keyword had only four references to where the term could be found (in a slip box containing over sixty thousand notes!). The assumption was the references in the notes would be enough to direct Luhmann where he needed to go once he entered the slip box.88

- Indexing is personal.93 Whether you choose to embrace Luhmann’s penchant for serendipity by creating a keyword index that only hints at what you’ll find, or decide to create something more comprehensive and explicit, the index you keep need only serve your purposes.

- Regardless of which approach you take, keywords need not only speak to topics and themes. They could also point toward emotions and experiences. If you want to feel your way through your ideas, you might include indexed references to “Ideas that make me laugh” or “Ideas that make me want to change the world.” You might also include references to repeated situations in which certain ideas arise: “Ideas that arise in therapy,” or “Morning walking thoughts.” So long as your index helps you engage with your zettelkasten, it’s a functioning index.

- Rather than structuring his zettelkasten around topical categories or as a hierarchical tree structure, Luhmann chose instead to allow his compartment of main notes to develop bottom-up, its structure emerging out of the relationships between ideas, sections emerging over time.

- There’s no need to be overly comprehensive with what you include in your high-level views. Let yourself be surprised by what you encounter.

- Clusters of ideas forming inside the zettelkasten are suggestions, not mandates.

- Imagine taking notes on a book about homesteading, thinking you’re going to write articles on the history of back-to-the-land movements in the United States, only to find the majority of the citations in your reference note came from a chapter on basket weaving. When the majority of your captures have to do with weaving baskets, even though you’ve ne’er a basket weaved, at some point you have to face facts: you’re interested in woven satchels. It’s in this way that reference notes show us our real interests as opposed to those that are mere wishful thinking.

- Structure notes provide a foundation for writing.

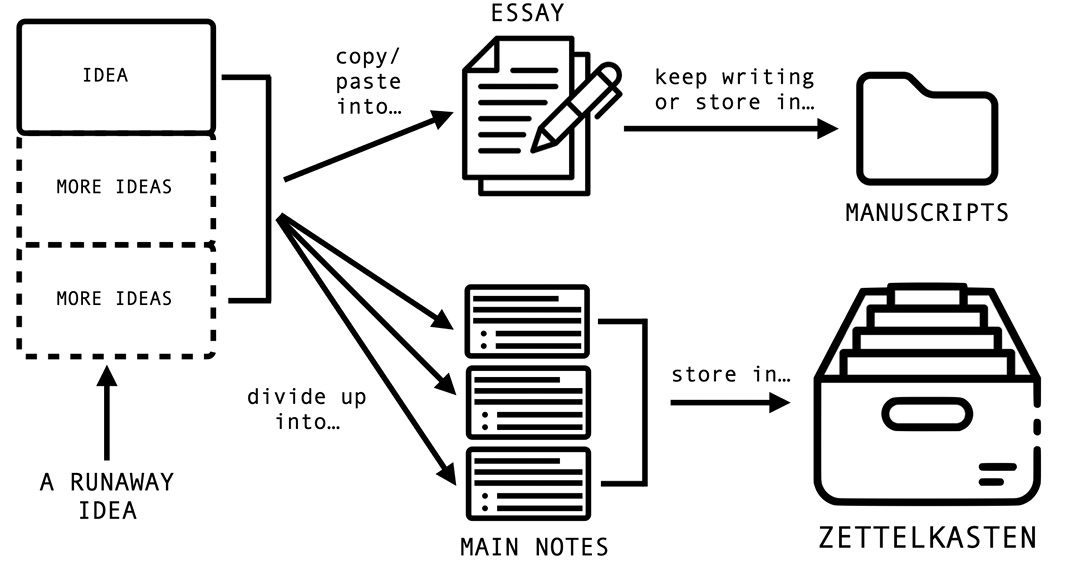

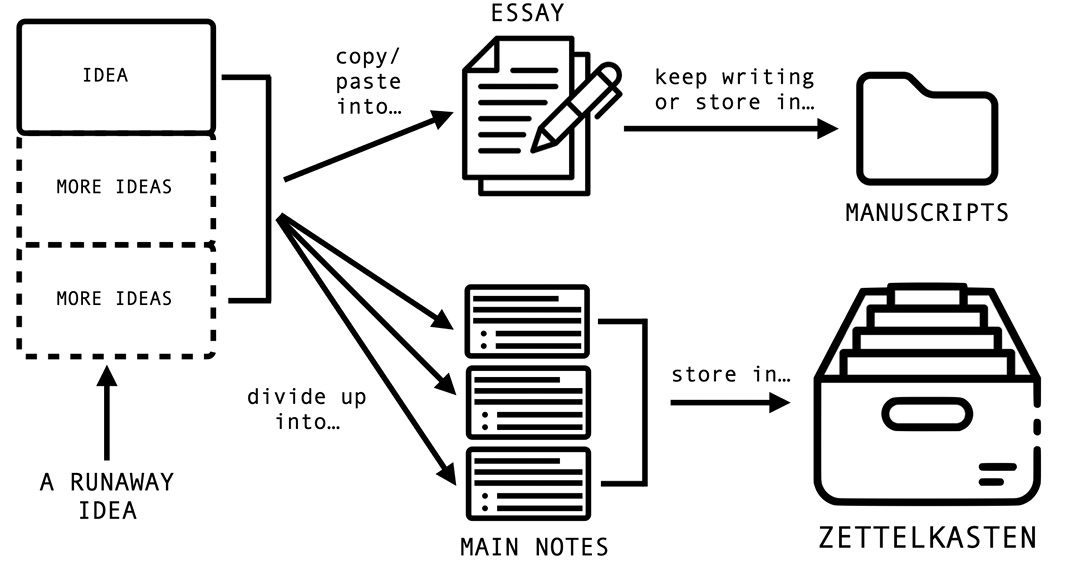

- Sometimes an idea just wants to move, so much so that any attempt to capture it in a single note proves a hopeless endeavor. Whenever I encounter a runaway idea, I have a choice to make:

• Break the long-note into several main notes, or

• Convert the long-note into an article

To make it easy, I do both (Fig. 46).

- Always take advantage of inspiration. If capturing an idea turns into writing an article, continue writing the article. After you’ve finished the piece or taken a break from writing, go back and find the ideas that didn’t make it into your zettelkasten, turning each one into a main note

- All the examples in this chapter show how a zettelkasten can point toward what to write about. None, however, suggest the zettelkasten should do the writing for you. And, the reason is simple: Your zettelkasten is a terrible writer.

The ideas you’ve been capturing in your main notes weren’t written in the context of any one specific piece of writing. These ideas need to be framed in light of the subject you’re writing about, the overall theme of the work, and your chosen tone. Ahrens reminds would-be writers to avoid copying notes into manuscripts, stating that writers should instead “[t]ranslate [ideas] into something coherent” by embedding the ideas “into the context of the argument.”98 This is advice worth heeding.

- Aside from unchecked (and undeserved) hubris, one of the reasons why working with a zettelkasten often leads to poor writing has to do with fragmentation, or as Richard Griffiths at writingslowly.com puts it, “the illusion that disjointed fragments can produce integrated thought.”123 Despite the connections you’ve made and the reasoning you’ve given for each one, relationships between ideas must be reframed in the context of the piece you’re working on. This means rewriting ideas, shaping them to express what you want.

- Your first paragraph can probably go.

- Lean into your footnotes and endnotes.

- Not every note in a train of thought need be brought into your manuscript.

- What you don’t include can be used elsewhere.

- • Take advantage of runaway ideas by transforming long, complex notes into rough drafts. Then parse out your ideas into individual main notes.

• Don’t let your zettelkasten write for you. Develop your writing craft by editing your ideas and unpacking and expressing the relationships between them.

- So long as your ideas remain hidden from view, they lack the substance that can only come from reader engagement. Meaning is created in community.127

- The easiest (and quickest) way to get feedback on ideas is to transform them into tweets, toots, and other short-short forms of online content.

- Do not use the convenience of main notes to “ship” prepackaged ideas. Get into the mix of discourse. Your zettelkasten is a catalyst, not a substitute, for creativity.

- one person’s procrastination is another person’s cognitive reset.

- Niklas Luhmann worked on multiple manuscripts simultaneously, which allowed him to avoid writing “blockages.”

- While some of the most well-known slip boxes in the world have been employed by writers in service of their writing,144 a zettelkasten can also be used without writing as an end goal.

Are SMART Goals Dumb?

Bibliography

Highlights

- Only 14% people say that their goals for this year will help them achieve great thingsOnly 43% of people set difficult or audacious goalsPeople who set difficult goals are 34% more likely to love their jobs.Top executives are 64% more likely to set difficult or audacious goalsTop executives are 91% more likely to enjoy leaving their comfort zone in pursuit of their goalsSetting a goal that requires learning new skills is nearly 10 times more powerful at inspiring employees70% of people indicate varying forms of procrastination (or a general lack of urgency for their goals)People who use visuals to describe their goals are 52% more likely to love their job People who set SMART Goals are far less likely to love their jobs